Portraits of ordinary people crafted by Kawahara Keiga, an Edo period Japanese painter in the service of German physician and botanist Philipp Franz von Siebold, are attracting renewed interest on the occasion of the 200th anniversary of Siebold's arrival in Japan.

Unlike Katsushika Hokusai and other ukiyo-e artists of his generation, Kawahara (1786-1860s?) learned the fundamentals of Western painting techniques from a Dutch painter and mixed them with traditional Japanese methods.

His unique realist style was fostered in Nagasaki, which was the only window to the West during the Edo period (1603-1867). Kawahara studied under painter Ishizaki Yushi, a master of the Nagasaki painting style.

In a time that preceded the development of photography, Kawahara's paintings were more realistic than his contemporaries, providing snapshots into the lives and times of the era.

"We can really appreciate the valuable materials that accurately depict the Edo period, which was completely different from our world today," said Masahide Miyasaka, 69, a visiting professor at Nagasaki Junshin Catholic University and expert on Siebold.

Kawahara also painted animals and plants, naturalistic landscapes, social scenes and many aspects of life at the Dutch factory of Dejima, an artificial island off Nagasaki, built in the 17th century by the isolationist Tokugawa shogunate as a trading post in southwestern Japan for the Portuguese and subsequently the Dutch.

Born in Nagasaki, Kawahara was hired by Siebold, who was serving as the resident physician of the Dutch factory, accompanying him on trips to Edo, the former name of Tokyo, and various other places like Kyoto and Nagasaki to document people. What is striking is the diversity shown among the common people he portrayed.

It is believed that Kawahara, in addition to being taught by Ishizaki, learned realistic painting techniques from a Dutch painter who had come to Dejima at Siebold's request after the German physician arrived in Japan in June of 1823.

When a delegation from Dejima, which included Siebold and Kawahara, visited the court at Edo, the painter documented objects and settings such as streets and court scenes.

Apparent in Kawahara's works, recent studies of Japanese history have rejected the notion of a fixed feudal social structure of samurai, farmers, artisans and merchants, and have shown that the Edo period was a society with a diverse mix of classes and religions.

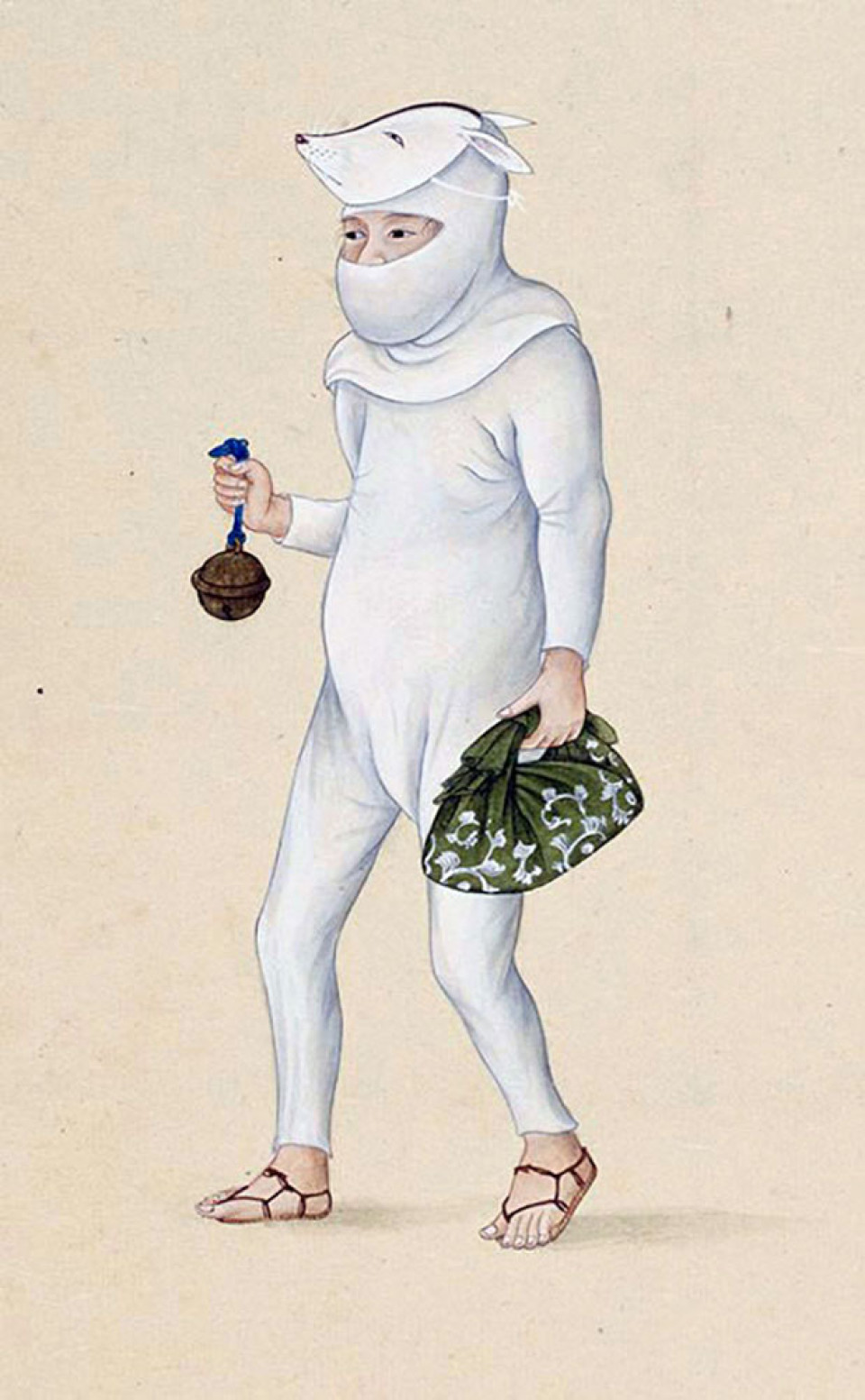

One of Kawahara's paintings, featuring a "fox-faced man" walking around dressed in a full-body white fox costume, depicts the people who pay homage to the "Inari" shrines, leaving "abura-age" (fried tofu) and other foods in bushes inside the compounds. Inari shrines are used to worship the god Inari, a popular deity associated with foxes, and abura-age is considered the god's favorite food.

There also remain paintings by Kawahara of whale-catching fishermen who were active in Wakayama and Kochi, as well as Nagasaki and Saga.

The "star fishermen" were famous for jumping onto the humps of whales in the rough winter seas to deliver fatal stab wounds. They were known to have distinctive topknots purposely grown long to make it easier to pull them from the water when they tired from the hunt.

Although Kawahara's portraits were published long ago, there have been no additional printings of his work produced and no current plans to release any soon.

Noting that Japanese people have become more Westernized since the Meiji era (1868-1912), Miyasaka, said, "We can see the Japanese people we have forgotten about" through Kawahara's paintings.

Although Siebold was funded with subsidies by the Dutch government for his research in natural science that included studying Japanese flora and fauna, one may wonder why he allowed Kawahara to draw ordinary people for purposes outside of work.

According to Miyasaka, Siebold wrote in an unpublished letter addressed to his family, "This civilization will disappear sooner or later and must be recorded."

Siebold possibly feared that Japan would lose its culture to the impending influx of Western civilization, made irresistible through the Industrial Revolution, Miyasaka said.

During his stay in Japan, Siebold also lived together with a Japanese woman and fathered a daughter, Kusumoto Ine, who eventually became the first female doctor in the country to be educated in Western medicine.

Kawahara was unfortunate in his later life. Preceded in death by his wife and two daughters, it appears the only person who may have been by his side was his son, also a painter.

A record book kept by the Nagasaki magistrate office named Kawahara as "a criminal" for his involvement in an incident where Siebold was accused of attempting to bring maps of Japan and other documents overseas and eventually expelled from Japan as a spy.

Chances are likely Kawahara was seen as a dangerous person and viewed with callous eyes by those around him in his later years before dying in obscurity.

Related coverage:

FEATURE: Noto quake cold deaths spark hypothermia public awareness drive

FEATURE: New rice dictionary cooking up lexicon for Japan's revered staple

FEATURE: New families sought for children with disabilities via adoption

By Hiroshige Shimoe,

By Hiroshige Shimoe,