Exposure to extreme cold temperatures caught many elderly people unawares in the wake of the Noto Peninsula earthquake that struck on New Year's Day, and their experiences have led medical experts to warn against the dangers of developing hypothermia -- even inside the home.

Generally speaking, people think of hypothermia as a condition that affects people outdoors. But the majority of its victims in Japan are senior citizens who freeze indoors -- sometimes due to crises caused by major disasters and other times for reasons stemming from their everyday lives.

Often, the annual death toll from hypothermia exceeds that of heatstroke. Doctors and experts are urging people beyond disaster-stricken areas in central Japan to take precautions against hypothermia regularly.

They also expect cases in the Noto region to raise awareness of the condition, which occurs when the body loses more heat than it generates.

On the night of Jan. 6, 124 hours after the 7.6 magnitude quake, a woman in her 90s was rescued from a collapsed house in Suzu city, Ishikawa Prefecture.

Although she had miraculously survived the ordeal, the woman's body temperature had fallen to 33 C. She was barely conscious as she whispered, "I'm cold..." After rescue workers warmed her up with hot water bottles for about three hours, she finally regained full consciousness.

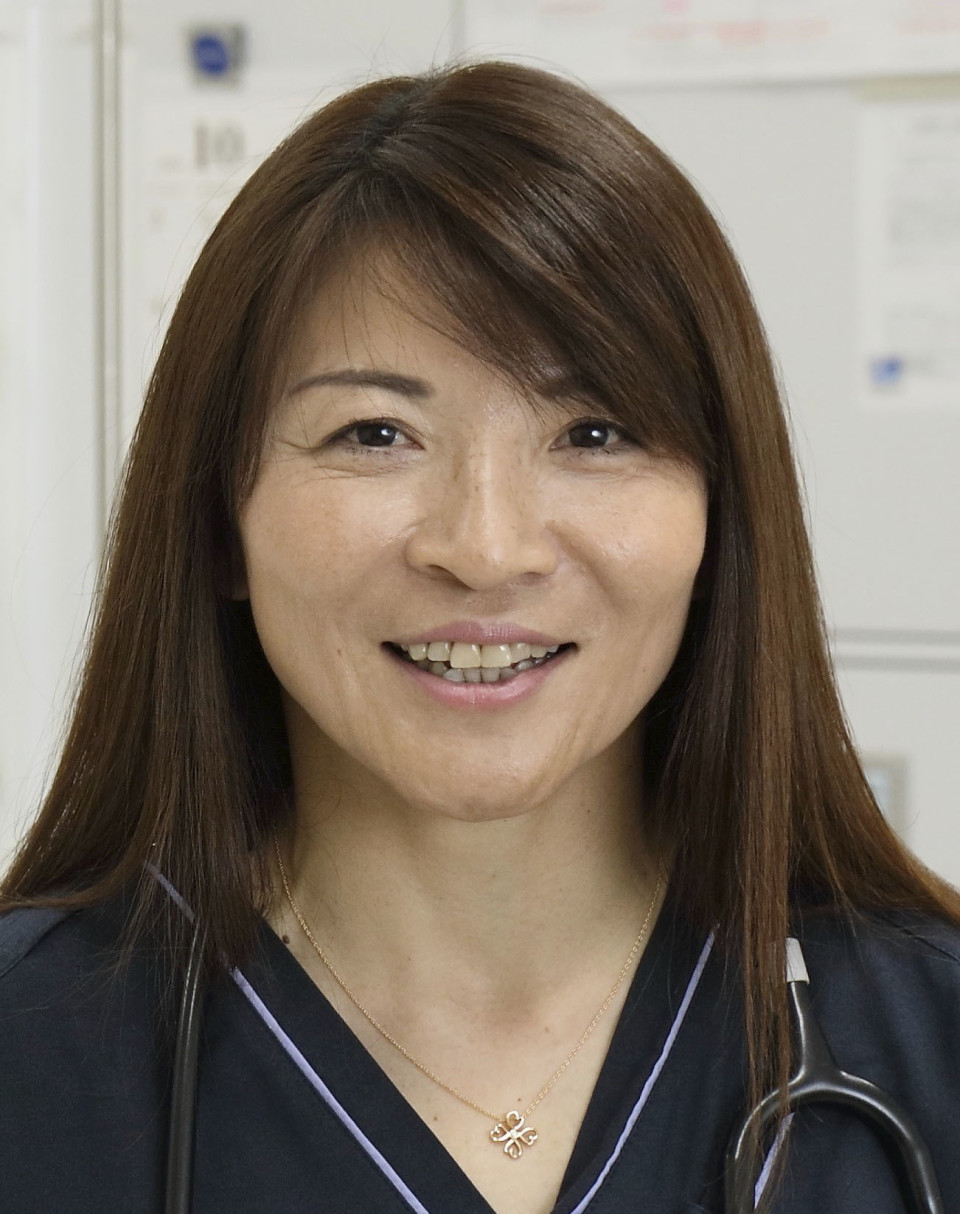

"It was a typical case of hypothermia," said Kazue Oshiro, an international mountaineering doctor.

"It's a condition in which the body loses heat due to cold and the body's core temperature falls below 35 C," she said. "Shivering and loss of consciousness may occur, and in severe cases, loss of consciousness may lead to death."

Tragically, that is exactly what happened to several earthquake victims. Police found that of the 222 Noto Peninsula earthquake fatalities they analyzed, 32 died of hypothermia or causes related to cold conditions.

Although this number indicates the severity of mid-winter disasters, most of the time hypothermia occurs "inside the home," even during ordinary times.

Nationwide surveys conducted by the Japanese Association for Acute Medicine from 2018-2020 found that roughly 70 percent of hypothermia cases happened indoors.

Of those, 80 percent were people aged 65 and older, while half of all cases involved worsening chronic diseases such as high blood pressure and mental illness, making it difficult for those affected to move around and keep warm.

The death rate was as high as 25 percent during the period, and cases were reported from all around the country.

In fact, the death toll from hypothermia is quite severe. According to the health ministry's vital statistics, the number has increased sharply in the country since the 1990s, and has exceeded 1,000 in most years since 2010.

There have been approximately 21,000 deaths from hypothermia in total from 2000 to 2022, compared with 17,000 for heatstroke over the same period.

"Even though this is the case, it really hasn't gained a lot of attention," pointed out Fumiaki Fujibe, a former specially appointed professor of climatology at Tokyo Metropolitan University, who has long studied the issues of heatstroke and hypothermia.

"There is a big contrast with heatstroke, for which awareness and countermeasures have progressed," he said. "Now, the earthquake has put a spotlight on hypothermia, but there are many elderly people who develop the condition in normal everyday life. We need measures and countermeasures at a societal level."

Oshiro, the mountaineering doctor, stressed the importance of individuals taking preventive measures to protect themselves against the cold and advised that people remember to try and keep their bodies warm, both "from the inside and outside."

"Wear multiple layers of clothing and cover your head and neck to prevent your body heat from escaping. Hot water bottles, which transmit heat directly to the body, are effective, easy to use and economical," Oshiro added.

One way to heat the body from the inside out is to make sure to "eat well and drink plenty of water," she said. "When calories are in short supply, it makes it harder for the body to produce heat."

Elderly people with chronic illnesses, in particular, tend to lose the ability to regulate their body temperature, and "many cases go unnoticed by others until they become seriously ill. It is important to watch over them and keep communicating with them," Oshiro said.

Related coverage:

Only 45 quake-hit foreign trainees in Japan allowed to do other jobs

Government to extend extra 100 bil. yen for quake relief in central Japan

Japan emperor mourns quake victims, hopes to visit disaster-hit areas

By Akio Nozawa,

By Akio Nozawa,

By Mei Kodama,

By Mei Kodama,