Hiroshi Harada was 6, waiting with his parents for a train at Hiroshima Station, when the atomic bomb exploded on Aug. 6, 1945, leveling the western Japan city.

His career would become entwined with that event, seeing him serve as director of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum from 1993 to 1997, a period which coincided with the blast's 50th anniversary and a controversial joint exhibition with the United States that brings him regret to this day.

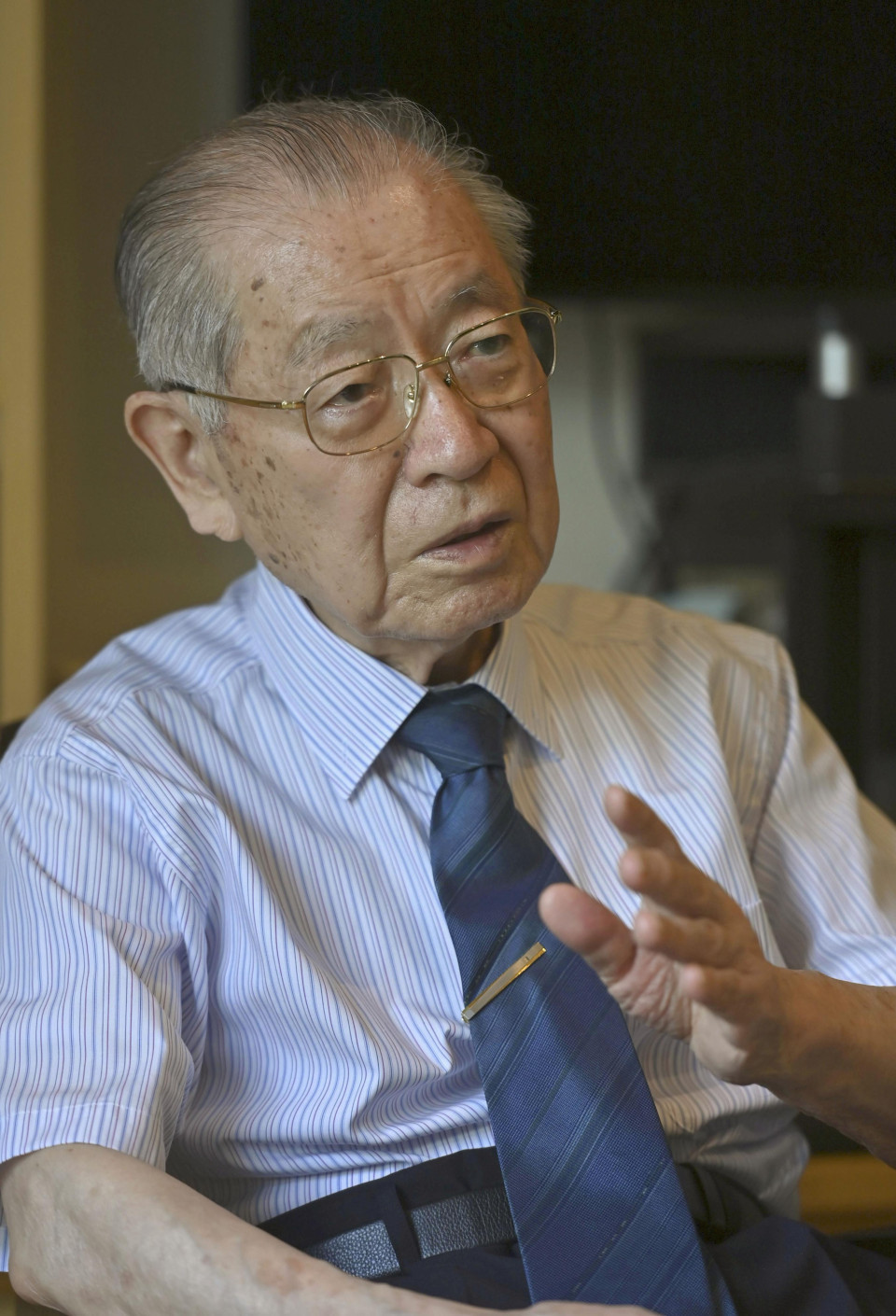

Reflecting on the moment Hiroshima and the world were brought into the nuclear age, the 85-year-old said, "At first there was a great light, but how it had emerged -- no one knew. People didn't know the horror that was coming for them."

At that moment, amid an intense heat, Harada says, his father instinctively used his body to shield him from the blast. He survived the impact largely unharmed.

"It was truly a miracle. Nearly everyone around the station was killed instantly," he said.

Harada briefly blacked out and when he returned to consciousness, the area around them had been largely destroyed, though the station's main building was one of the few structures still standing.

"Without it, we would have been directly exposed. The heat near the hypocenter was around 4,000 C," he said.

With the flames encroaching, his father said they should run. They headed east through the ruined city, and in their haste to survive, they were left with no choice but to run on top of the mass of people who had collapsed in the street.

"I didn't know if they were dead. We did that to save our lives," he said. "It still pains me to think, why did I have to step on other people's bodies to save myself? It's something I don't like to think or talk about."

In 1963, Harada became a public servant working at the Hiroshima city government, later rising to the position of director of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, which is dedicated to preserving memories of the atomic bombing.

Artifacts on show at the facility include clothes belonging to children who died from burns caused by the bomb, pictures and drawings of victims and other effects belonging to people who lost their lives as a consequence of that day.

But an unsuccessful collaboration for a 50th-anniversary exhibition in the United States during his tenure weighs on his heart.

The plan, in the making for years, would have seen the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum exhibit the Enola Gay B-29 bomber that dropped the Little Boy atomic bomb on Hiroshima, alongside objects melted in the blast and testimony from survivors.

"(Then Director Martin Harwit) believed it wasn't enough just to say that America won because of the atomic bombing. He believed what happened on the ground due to the bombing needed to be conveyed, too," Harada said. "But in America, it was taken as a rejection of the atomic bombing."

The plan drew a strong backlash from a U.S. Air Force veterans group, while opposition was also aired by lawmakers in the U.S. Congress. Harwit eventually resigned in May 1995.

Ultimately, the exhibit went ahead in June of that year, showcasing the fuselage of the Enola Gay, but without any articles donated from Japan to offer perspectives on what it was like to be on the receiving end of its destructive power.

"All I can say is that it was utterly regrettable," Harada said, adding, "I went to the museum several times and seeing inside made me painfully aware that the museum was meant to show a history of glory."

"There wasn't a desire to think about the effects of the bomb. It made me feel we still have work to do to convey what happened, and that if we do, it could lead to an end to nuclear weapons," he said.

While Harada has guided many dignitaries around the Hiroshima museum, he has fond memories of meeting then Emperor Akihito and Empress Michiko in 1995. During the tour, the imperial couple turned to Harada, asking him to describe his experiences of the bombing.

"Once I started speaking, they kept their gazes fixed on me as they listened," he recalled. "I think it made a strong impression on them as they heard how awful the bombing was."

About two months later, when the imperial couple was back in Hiroshima for a visit to remember the atomic-bomb dead, the emperor sought him out to thank him for their previous meeting. He urged Harada to take care of himself as he made efforts toward peace.

"I hadn't expected it and didn't know what to say to the emperor in that situation, so I was lost for words," Harada said.

The number of atomic bombing survivors continues to fall with the passing years, down to 106,825 government-recognized survivors as of the end of March from a peak of 372,264 in March 1981, according to health ministry data.

Many have died without their wish to see a world without nuclear weapons realized, and various conflicts, including in Ukraine and the Gaza Strip, have led to a rise in global tensions.

And while the total number of nuclear warheads continues to fall, operational warhead numbers are rising, up by nine to an estimated 9,585 as of January from a year earlier among nine states, including nuclear powers the United States and Russia, and de-facto nuclear states such as North Korea, the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute's annual report issued in mid-June showed.

"Around 140,000 lives were lost to the Hiroshima bombing, and around 70,000 of them are still unidentified...For their sake, atomic bomb survivors and people the world over must take action to eliminate nuclear arms," Harada said.

Related coverage:

FEATURE: Nagasaki survivor-doctor works for nuke-free world into his 80s

Hiroshima survivor who broke silence at 70 seeks "blue sky" of peace

By Mei Kodama,

By Mei Kodama,